In 1969 I went to Japan in search of Zen. There I met Kosho Uchiyama, abbot of Antaiji Temple. It was neither my first meeting with a Japanese Zen teacher nor was it my first stay at a Zen temple in Japan, but it was a special meeting for me because it was my first meeting with a Zen teacher who seemed to have none of what I will call ‘Zen posturing’. Our discussion was informal and I walked away feeling that I had met someone who could be a friend as well as a teacher. Uchiyama invited me to stay at Antaiji and I did.

Sodo Yokoyama

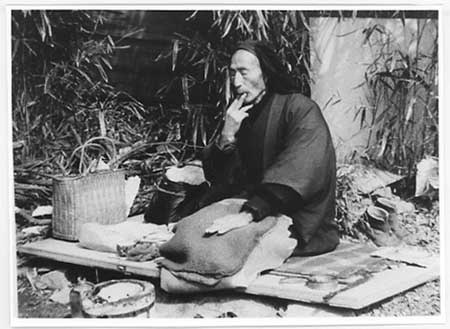

During my stay at Antaiji I came into contact with five teachers of Zen. Three, I met, and two I learned of through their heirs and their writings. All of these teachers were, in some capacity, connected with Antaiji, a small poor temple in Kyoto that seemed to be a magnet for Zen figures who did not mind breaking with tradition. The most unique of these teachers was a poet monk named Sodo Yokoyama.

Yokoyama sat in a park practising zazen and inspiring travellers. If traditional Japanese dance is poetry in motion, Yokoyama’s upright sitting posture was motionless poetry. Many took his photograph and were encouraged by the image of this monk whose practice was to follow his heart. As one woman who brought Yokoyama a coat that her mother weaved for him said, ‘My dad is a Zen priest, but he has a family. He cannot live the life of pure Zen like Yokoyama Roshi does. We wanted to show our appreciation to Roshi for upholding the Way.’

Yokoyama played tunes that he composed by blowing them on a leaf. For Yokoyama, leaf-blowing signified the freshness of youth. He said that only children try to get tunes from blowing into a leaf; adults have no time for such playful activities. As long as he blew the leaf, he was reminding himself that the playfulness of youth should never disappear. He also felt that one would never get a perfect tune from a leaf, that it was an instrument for amateurs, and there lies its charm.

Twenty years after leaving Antaiji, I began to write Living and Dying in Zazen—a story about my experiences there. All of the teachers I was writing about with the exception of Uchiyama had died. I had met Yokoyama in his ‘Temple Under the Sky’ during the time I was practising at Antaiji, but I knew little about his final years. In order to learn more about this period in his life, I sought out his only disciple, a monk named Joko Shibata. I wrote about my meeting with Joko in a previous issue of Buddhism Now. After that meeting I have visited him whenever I have returned to Japan.

Joko Shibata

Joko lives in a small town in Northern Japan called Komoro City. His house is about twenty minutes by car from the park where his teacher practised his unique form of Zen. Joko sits facing a wall practising Zen meditation for most of his day. He seems to be in perennial sesshin. When he is not sitting he is cooking meals, studying Buddhism or attending to his garden. The garden is small and somewhat neglected, ‘It’s like this because I spend too much time doing zazen,’ he says with a chuckle. But he seems to feel that his priorities are correct. Like his teacher, Joko places zazen at the top of his list of preferences.

This year I visited Komoro City with my daughter. I wanted her to see Northern Japan and thought it would be nice to have her meet Joko. She has no particular interest in Buddhism. Joko lives for Buddhism and loves to talk about it. Though I knew my daughter Nao would not be excited about a discussion on Buddhism, I felt that Joko’s vivaciousness and warmth would win her over. I was right.

We arrived at the Komoro train station an hour earlier than our appointed time to meet Joko. The station was adjacent to the park where Yokoyama Roshi had his ‘Temple Under the Sky’. I hadn’t visited the park since my 1972 meeting with Yokoyama. I decided to take Nao through the park with the hope that I would remember where Yokoyama sat and played his music. It was more than thirty years since my last visit.

We arrived at the Komoro train station an hour earlier than our appointed time to meet Joko. The station was adjacent to the park where Yokoyama Roshi had his ‘Temple Under the Sky’. I hadn’t visited the park since my 1972 meeting with Yokoyama. I decided to take Nao through the park with the hope that I would remember where Yokoyama sat and played his music. It was more than thirty years since my last visit.

We walked around as I stretched my memory trying to remember where the spot was. Yokoyama had been dead for twenty-four years and I wondered how many present-day travellers at the park knew of his unique life in the park. As we got closer to the spot, I recognised the place, not so much with any conscious memory but simply with a feeling. I didn’t fully trust the feeling, but then I saw a flat rock upright with something inscribed on it. It was a calligraphy of a haiku poem about Yokoyama. It was a calligraphy that Yokoyama had brushed many times. I have one which I received from Joko and which is now hanging in my room. It translates:

We walked around as I stretched my memory trying to remember where the spot was. Yokoyama had been dead for twenty-four years and I wondered how many present-day travellers at the park knew of his unique life in the park. As we got closer to the spot, I recognised the place, not so much with any conscious memory but simply with a feeling. I didn’t fully trust the feeling, but then I saw a flat rock upright with something inscribed on it. It was a calligraphy of a haiku poem about Yokoyama. It was a calligraphy that Yokoyama had brushed many times. I have one which I received from Joko and which is now hanging in my room. It translates:

The floating cloud monk

Plays the leaf sadly

Chikuma River

Chikuma River runs through the park at the back of the area where Yokoyama sat.

A short distance from the rock was a box. Above the box was a photograph of Yokoyama and a short statement about his life in the park. There was a button of some kind on the box. I was excited and Nao needed very little explanation. I didn’t have to say, ‘Here’s where he sat,’ etc. It was quite obvious. She could see that I was choked up, and she remained silent. Then, like a curious kid, I pushed the button. From the box came a recording of Yokoyama playing the leaf followed by him singing. This bit of modern technology as a part of a memorial for this very classical monk, was a little eerie, and yet this funky music and song told more about this very special monk than could volumes of the written word.

A short distance from the rock was a box. Above the box was a photograph of Yokoyama and a short statement about his life in the park. There was a button of some kind on the box. I was excited and Nao needed very little explanation. I didn’t have to say, ‘Here’s where he sat,’ etc. It was quite obvious. She could see that I was choked up, and she remained silent. Then, like a curious kid, I pushed the button. From the box came a recording of Yokoyama playing the leaf followed by him singing. This bit of modern technology as a part of a memorial for this very classical monk, was a little eerie, and yet this funky music and song told more about this very special monk than could volumes of the written word.

This article first appeared in the November 2004 Buddhism Now.

Other posts by Arthur Braverman

————————

I recently visited Kaikoen Park in Komoro, Nagano. I wanted to visit the place Sodo Yokoyama, a Zen monk, would sit every day, serving people tea, writing calligraphy and playing the leaf flute.

This is a video of photos taken at the park, along with a recording of Yokoyama’s leaf music (there is a small electronic box at the park which plays his music, he died in 1980).

By airbarracuda.

Categories: Arthur Braverman, Biography, Buddhist meditation, Chan / Seon / Zen, Encyclopedia, History, Mahayana, Video

Thanks for sharing such profound life (just a stage of being) in my opinion. Very touching in my heart to have read this article. Thanks for sharing.

The holy breath of the great Bodhisattvas of the past fills our present with its music. My sleeves are wet with tears for their great tenderness to us.

Beautiful article. I especially resonate with the parts concerning the leaf flute